Audi Quattro – review, history, prices and specs

Here is everything you need to know about the Ur-Quattro, the short-wheelbase Sport Quattro and the 20V

The importance of the Audi Quattro should not be underestimated. Not only is it the car that established Audi’s reputation for creating fast, secure, desirable, well-built cars, but in one fell swoop it revolutionised rallying with its four-wheel-drive system while normalising all-wheel drive in road-going performance cars.

The original Audi Quattro is now often called the Ur-Quattro to help differentiate this boxy coupe from Audi’s four-wheel-drive system (quattro with a small ‘q’) and later four-wheel drive models. The ‘Ur’ is a German prefix meaning earliest or original.

> Find out how the Audi Quattro 20V compares with a new Nissan GT-R

Given that today Audi is synonymous with four-wheel drive, it seems odd that back in 1976, when Ingolstadt engineers first started thinking about an all-wheel-drive performance road car, the idea was met with resistance. Before the Audi Quattro, four-wheel-drive cars were mostly robust, industrial off-roaders or heavy and clunky road cars. Most of them, even the all-wheel-drive Jensen Interceptor FF, used a bulky and old-fashioned transfer box to split torque between the axles, a concept that didn’t fit with Audi’s philosophy for making sophisticated, high-tech cars.

To get the Quattro project started, Audi engineers created a mule from a two-door Audi 80, fitting it with the drivetrain from a VW Iltis, a military-spec 4x4 developed by Audi. The mash-up was demonstrated to Audi and VW board members and its abilities in snowy conditions convinced them, including Audi’s then head of research and development, Ferdinand Piëch, that it was certainly effective, even though they weren’t sure that it would be a sales success. Nevertheless, they gave the go-ahead for the project.

But the prototype vehicle was far from perfect. Like contemporary all-wheel-drive Subarus it didn’t use a central differential, and this meant its low-speed behaviour was crude and jumpy. This was deemed unacceptable to Audi, as were the results achieved with a transfer box. So the Quattro’s engineering team, led by Jörg Bensinger, then Audi’s manager of experimental running gear and today known as the father of the Quattro, set about trying to create a low-weight, four-wheel-drive system with a central differential that would eradicate the undesirable low-speed characteristics and be neater and lighter than a transfer box.

> Read our review of the modern day Quattro, the Audi RS5

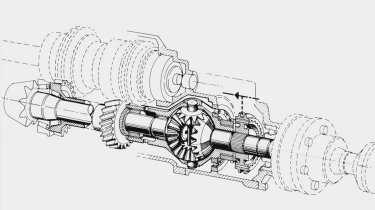

But finding the best place to put the diff was tricky. Audi’s selection of in-line-engine, transaxle front-wheel-drive layouts – with the engine positioned well ahead of the front axle – were the perfect platforms to adapt to four-wheel drive, as a propshaft could be taken straight off the back of the gearbox to the rear axle. Put a diff at the back of the transmission, though, and you have to find a way of sending drive back to the front axle through or around the ’box.

Bensinger’s team, including transmission experts Hans Nedvidek and Fran Tengler, came up with the idea of making the gearbox’s output shaft hollow. This shaft would turn a diff mounted behind the gearbox, then another shaft inside the hollow shaft would send drive back to the front axle. Meanwhile a further propshaft would send drive from the central diff to the rear axle.

The prototype cars used the tiny differential from a Polo-based Audi A50, the smallest car Audi made at the time. It was just an open diff with no way of controlling torque, so to allow drivers to really exploit the car’s four-wheel-drive traction, cable-operated diff locks were added to the rear and centre differentials. It was an evolution of this set-up that made its way onto the first Quattro road cars, with the locks activated by a switch on the centre console.

The four-wheel-drive system, and the traction it generated, meant the Quattro could really make the most of a turbocharged engine. Two-wheel-drive turbocharged cars, including Audi’s 200 model that had been billed as ‘the world’s most powerful front-drive car’ thanks to its 170bhp 2.1-litre five-cylinder engine, were considered a bit wild and unruly. The first Quattro, however, with the same engine as the 200 but with an added intercooler and 30bhp more, was stable and secure as well as fast.

Audi Quattro in detail

The Quattro’s power output doesn’t seem all that impressive now, but its 200bhp combined with four-wheel drive made it supercar-fast by the standards of 1980. The contemporary Porsche 928 and Ferrari 308 GTB may have had around 50bhp more and looked a lot more like conventional sports cars, but where period road tests recorded 0-60mph times of 7.2sec and 6.5sec respectively for those two (the former in automatic form), a Quattro was timed at just 6.3sec over the same sprint.

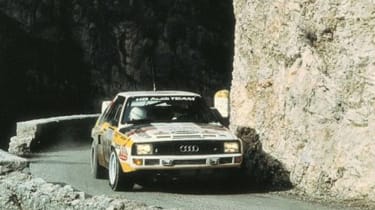

The combination of all-wheel-drive traction and turbocharged power was also what made the Quattro so competitive in rallying and, initially, almost unbeatable on rough and loose surfaces. Driving Quattros, Hannu Mikkola and Stig Blomqvist won the 1983 and 1984 World Rally Championships respectively, and Audi took the ’84 constructors’ title. It wasn’t long before other manufacturers jumped on the bandwagon and created all-wheel-drive contenders, helped by the recently introduced Group B regulations that required just 200 road-going examples of a model to be built for it to be eligible to compete.

Rave reviews and competition success meant that demand for the Quattro was high in the early ’80s, but it wasn’t until 1982 that Audi built the first right-hand-drive versions – up until then the UK had to make do with left-hand-drive cars. British customers had to wait again for ABS, as this wasn’t available on RHD cars until 1984, whereas LHD cars were so equipped from 1983. Incidentally, it took some development to get the ABS to work effectively with the Quattro’s all-wheel drive, the result being that it would automatically turn off when the diff locks were engaged – themselves now pneumatically operated locks rather than cable. Audi also gave drivers the option to disable ABS via a switch on the dash.

While the regular road car received a few minor tweaks over the years, the rally car was transformed more dramatically. To enable it to compete with rivals like the mid-engined Peugeot 205 T16 and Lancia Delta S4, in 1984 Audi chopped 317mm from the Quattro’s wheelbase to make it more agile, while an all-alloy 20-valve double-overhead-cam engine was developed to make it significantly more powerful (over 500bhp was achieved).

The short-wheelbase rally car was known as the S1 Quattro, but at least 200 road-going cars needed to be produced to homologate it. To this end, Audi created the Sport Quattro, a short-wheelbase road car that was sold at over twice the price of the ‘long’ one. This stubby little car with 302bhp and 258lb ft of torque might have looked absurd, in the best possible way, and be full of race car-like details – Kevlar reinforced body panels, a larger intercooler and a huge turbo – but it retained much of the original Quattro’s stability and on-road manners.

Sadly, even though Audi was at the forefront the revolution taking place in rallying, the S1 wasn’t able to challenge the more extreme, purpose-built Group B cars. It took occasional wins, but the ’85 and ’86 championships went to Peugeot before Group B was outlawed completely.

Rather than just benefitting the limited-run homologation special, the improvements Audi made to the Sport Quattro filtered down into the production Quattro. In 1989 the Quattro 20V was launched, with an all-aluminium 220bhp engine using a new four-valves-per-cylinder head. The drivetrain was given a significant update, too. The central differential was swapped for an automatically locking Torsen unit. It suited the Quattro so well that Bensinger said: ‘Had we known about the Torsen differential then, it almost certainly would have been on the original Quattro.’

In 1991 production of the Audi Quattro came to an end. It might have been directly replaced by the Audi S2, but the concept, character and technology that debuted on the Quattro had already begun to infiltrate every one of Audi’s models. By 1984 Audi offered a quattro version of every model it sold – a tradition that continues today, with everything from the A1 to the R8 being available with four-wheel drive. They may not all have the same longitudinal-engine and centre-differential layout as the Ur-Quattro, but the philosophy of added traction and stability through all-wheel drive is still abundantly apparent.

The evo view

Audi Quattro in the Alps – Harry Metcalfe (evo issue 079)

We find a superb road that starts with fast open sweepers that climb through a wooded section, before the corners start arriving in quicker succession and begin to tighten, hugging the mountainside for comfort. This is Quattro territory all right, the occasional damp surface, punctuated by shallow rivers of melting snow, making no difference to our progress. I’m revelling in the ability of the car to dispense with the short straights and its astonishing poise through the corners, allowing you to apply the turbo power earlier and earlier as you learn to trust the all-wheel drivetrain to sort it out. Until, that is, it all goes suddenly, horribly, nastily wrong.

One of the unfortunate side effects of the Quattro’s surefootedness is that is can give you the belief that you are invincible, when physics, of course, dictate that you’re not. As we power down a brief straight there’s a rock face fast approaching to my right that is shading the road beyond. What lurks in its shadow is a glistening surface of packed snow which I’m about to strike at a pace you’d normally reserve for a suicide attempt. This has all the makings of the biggest, most embarrassing moment of my life.

Desperately I try to scrub off some speed, as there’s plenty I need to dispense with, but without the assistance of ABS (later cars had it, but this one doesn’t) pumping the brakes just locks the front wheel on the sheet ice. Oh sh*t. There’s oncoming traffic to contend with too, forcing me to come off the brake briefly to regain some steering to pull the nose round. As the last approaching car exits left, there’s an unwanted corner fast approaching that I really can’t see us making. Oblivious to the impending catastrophe the Quattro skews gently sideways, and with a little flick of opposite lock we somehow scrabble through the bend without hitting the barrier. Right now there isn’t another car I would rather be driving.

Audi Quattro 20V at Anglesey – Jethro Bovingdon (evo issue 194)

The Quattro feels nothing short of vintage these days: narrow, soft, quiet and relatively slow. However, a sopping wet track allows the old magic to shine. The Quattro is predominantly an understeerer, but with the freedom to brake into turns and use weight transfer to help balance the car, it reveals a degree of adjustability. It washes wide through the first, hellishly slippery right-hander (we’ll later discover most cars do) but it’s terrifically agile into the tricky downhill braking zone that follows, the rear stepping out and then holding a lovely angle as you get gently back on the power to balance the car.

Through the Corkscrew the Quattro again falls into understeer, but it isn’t speed-destroying and the line tightens under power through the long following right at School, the Quattro taking full throttle pretty early and staying really neutral. Into the tight left of Rocket with a lift and the rear steps out just a little, meaning you can give it the full Scandinavian flick into the hairpin and pin the throttle to make the most of the tight line. It’s actually superb through here and it’s a great end to a tidy lap.

Audi Sport Quattro at Bedford Autodrome – Jethro Bovingdon (evo issue 088)

Twist the key and the in-line five churns slightly reluctantly to life. It’s a bassy, busy noise, but at idle there’s little hint of what’s to come. The conventional five-speed ‘box (no dog-leg) is pretty horrendous. The throw is comically long, and the shift from second to third almost has you punching the passenger door. But that’s about where the criticism ends.

Of course, there’s plenty of turbo lag, but even off boost the 2.1-litre engine feels pretty perky. Hit 4000rpm and the boost gauge springs into life, while that unmistakable warble seems to infect every fibre of the car. The power, which feels easily as strong as the 306bhp claim, just keeps growing, and because it’s pretty long-geared the journey to over 7000rpm can be savoured. Even deep into fourth the Sport feels genuinely rapid.

There’s textural steering feel – something that not even an RS4 can really claim – and the strong brakes are full of feel, with their assistance perfectly judged.

We took the Sport to Bedford Autodrome to see how it performed at its limits in a risk-free environment. Driven hard but with a degree or two more mechanical sympathy than we would afford a brand new press car, the Quattro turned in a lap time less than four seconds behind a [then] new B7 RS4 – and I’m sure you could close the gap even further if you forgot exactly what you were driving.

> Read our buying guide for the Audi B7 RS4

The power is directed 50:50 front:rear, but the short wheelbase makes the Sport a lively, interactive machine. Lift-off as you turn in and the tail edges wide; brake late and deep into a corner and the rear jinks left and right, keeping you on your toes.

Although the ABS dramatically increased stopping distances if you triggered it, the brakes didn’t fade at all. The car also demonstrated remarkable resistance to understeer. With the full Scandinavian flick the Sport would oversteer from entry to exit. Brilliant!

What to pay

Audi Quattro £20,000 – £40,000

Audi Quattro 20V £30,000 – £50,000

Audi Sport Quattro £250,000 – £350,000

|

Quattro (1998 UK) |

Quattro 20V |

Sport Quattro | |

|

Engine |

In-line 5-cyl, 2226cc, turbo |

In-line 5-cyl, 2226cc, turbo |

In-line 5-cyl, 2134cc, turbo |

|

Max power |

200bhp @ 5500rpm |

220bhp @ 5900rpm |

305bhp @ 6700rpm |

|

Max torque |

211lb ft @ 3500rpm |

228lb ft @ 1950rpm |

258lb ft @ 3700rpm |

|

Transmission |

Five-speed manual, permanent four-wheel drive, manually locking centre and rear differentials |

Five-speed manual, permanent four-wheel drive, Torsen limited-slip centre differential, manually locking rear differential |

Five-speed manual, permanent four-wheel drive, manually locking centre and rear differentials |

|

Front suspension |

MacPherson struts, coil springs, anti-roll bar |

MacPherson struts, coil springs, anti-roll bar |

MacPherson struts, coil springs, anti-roll bar |

|

Rear suspension |

Independent struts, coil springs, anti-roll bar |

Independent struts, coil springs, anti-roll bar |

Independent struts, coil springs, anti-roll bar |

|

Steering |

Rack and pinion, PAS |

Rack and pinion, PAS |

Rack and pinion, PAS |

|

Brakes |

Vented discs, ABS |

Vented discs, ABS |

Vented discs, ABS |

|

Wheels |

8 x 15in |

8 x 15in |

9 x 15in |

|

Tyres |

215/50 R15 |

215/50 R15 |

235/45 R15 |

|

Kerb weight |

1331kg |

1380kg |

1273kg |

|

0-60mph |

7.0sec |

6.5sec |

4.8sec |

|

Max speed |

135mph |

141mph |

155mph |