My Life & Cars – Julian Thomson, Automotive designer

Starting out sketching cars in his schoolbooks, Julian Thomson has gone on to work on many an iconic automotive shape – and has owned his fare share too

Not all car designers are diehard car enthusiasts. But rather like fat chefs, you’re more inclined to look favourably upon those whose passion for their chosen profession extends beyond the nine-to-five. Julian Thomson, most famously the designer of the Lotus Elise S1 and who has helped steer the reinvention of Jaguar’s styling for the past 21 years, is completely immersed in car culture, outside and inside of work.

He sketches cars and sees them into production; he appreciates our automotive past and contemplates its future; he owns a wholesome stable of interesting cars, modifies them, restores them and drives them often; he frequently attends car events and takes pictures of what he sees – whole cars and design details – for his own entertainment. He even claims to be an early adopter of the trackday movement: ‘Back in the early ’80s my mates and I hatched a plan in the pub. Someone had discovered you could rent the Goodwood Circuit for £125, plus another £125 for an ambulance. We worked out that if we got 25 people together, it’d cost us a tenner each.

> My Life & Cars – Peter Stevens, car designer

‘In the event only three of us turned up in our crappy cars – me in my Fiat 124 Spider and two friends, one in a Lancia Beta Monte Carlo and the other in his Alfa Giulia Spider. So we had the whole of Goodwood for the day and went round and round and round until our cars blew up! We were pioneers of the trackday thing.’

Thomson’s interest in cars doesn’t stem from any family influence – ‘My mum drove a Mini van, my dad a Bedford minibus’ – but from an early age it was all-consuming. ‘The margins of my school exercise books were covered in little sketches of cars and this was very much to the detriment of my school work,’ Thomson confesses. ‘And me and my brothers used to make Airfix, Revell and Monogram plastic car kits; we were pretty keen on taking them apart and inventing our own cars from the bits.’

They may not have been car folk, but Thomson’s parents were very supportive of his drawing. ‘They encouraged us to draw as much as we possibly could. My father spent the majority of his working life as head scientist of The National Gallery in London and was passionate about art. But he actually didn’t believe you could teach it; he thought that art was a natural talent that you were born with. He wasn’t keen on art school. He thought it was better just to keep drawing.’

And Thomson did. Mainly cars. With the goal of becoming a car designer. Back in the early 1980s, however, the only sure-fire route to becoming such a thing was to take the Royal College of Art’s Automotive Design qualification, a postgraduate course. Knowledgeable souls advised the teenage Thomson that the best path to get to that point was via an engineering degree. ‘It was very, very difficult,’ he admits, ‘because I was still academically appalling, dismal.’

The engineering course wasn’t without highlights, however. For instance, there was a three-month work placement at Rardley Motors, a Ferrari specialist. ‘This experience cemented my love for Ferraris,’ beams Thomson. ‘We had all sorts of cars through the workshop, including a 250 GTO that this guy had just paid £125,000 for – we were outraged at the price. There was another guy who had an ex-Le Mans Daytona that we drove on the roads around Hindhead with straight-through pipes.’

But it was an internship at Ogle Design that suited Thomson’s career ambitions much better, and simultaneously demonstrated to him the importance of making good contacts. In 1980 the then 17-year-old had entered a competition in a motoring magazine to design a new MG, winning himself a highly commended prize in the (over 18s) adult category. At the prize-giving he met Ogle Design’s Tom Karen (designer of the Bond Bug three-wheeler and original Reliant Scimitar). ‘At Ogle Design I learnt how to draw properly, learnt the technique for designing cars.’

Ogle’s tuition proved invaluable. ‘After I’d finished the engineering degree I put together a portfolio and presented it to the Royal College of Art,’ recalls Thomson. ‘I thought I’d done OK, but later discovered that the course sponsors – Ford, Chrysler and Austin Rover – had had a fight about who was going to take me on. Turned out I was the top choice. So after struggling academically for years, I was going to the Royal College of Art to learn how to draw cars – I couldn’t believe it.’

Meanwhile Thomson had been making his way through some interesting cars. He learnt to drive in his mum’s Renault 5 GTL, then bought a second-hand Alfasud 1.2 Ti which ‘reverted to soil’ very quickly. A Fiat 127 Sport followed, and after that the 124 Spider that he still has in storage, then a 131 Mirafiori Sport that he greatly enjoyed. His buying choices were all heavily influenced by the outcomes of road tests in Car magazine.

As Ford was his sponsor at the RCA, Thomson did his internship at the company’s design studio at Dunton, where the designer assigned to mentor him was Ian Callum, who was to become his friend and later his boss for many years at Jaguar’s design studio. Thomson graduated from the RCA in 1982 and observes: ‘Back then there were really only two colleges in the world turning out car designers – the RCA and the Art Center in Los Angeles. Between them they produced fewer than 25 car design graduates a year, so we all got very good jobs. These days there are hundreds of graduates from many colleges globally.’

Although Ford in the early 1980s had a very swish design studio, work didn’t pan out quite how our newly qualified car designer had envisaged. ‘That myth you hear about car designers stuck doing things like door handles and not really contributing to the battle plan? It was a bit like that,’ he sighs. ‘One bored afternoon I counted the number of strip lights on the ceiling – 928 of them, which I remember because of the Porsche.’

Out of hours, Thomson’s motoring landscape was looking brighter. After an original Ford Fiesta XR2 and a VW Golf GTI had sparked a life-long fascination with hot hatches, in 1985 he was fortunate enough to receive an inheritance. Rather than stick it in a building society, he bought a £13,000 Ferrari 246 Dino. Good man. And because a housemate was Lord Brockett’s brother, he was able to ‘borrow’ the then peer’s personal Ferrari mechanic, Jim, to check over the Dino and get it running properly. ‘Although the classic car scene back then wasn’t what it is now, it was an unusual thing to have,’ reckons Thomson. ‘People in the know realised it was a cool car, but to the rest it was just an old car.’

Insufficiently challenged at Ford, Thomson again experienced the value of contacts. ‘My old college tutor, Peter Stevens, approached me about setting up Lotus Design, so I went to Norfolk. I arrived for my first day and they’d rented a Portakabin for us to design in, and the back half was yet to be delivered! To this day I wonder why I wasn’t shocked but I thought it was great. It was Lotus.

‘I loved working there. At Lotus you got to know everyone; you got to know all the different disciplines. You knew the people in manufacturing, ride and handling. I became very good friends with Roger Becker and his son Matthew – there were so many great friendships I made there. My first big break was doing a show car for Isuzu [Lotus Engineering was a design consultancy, amongst other things] called the 4200R, highly acclaimed at the 1989 Tokyo motor show.’

After several years at Lotus, during which time Stevens departed and the company’s ownership changed from General Motors to Romano Artioli’s Bugatti, Thomson was promoted to head of Lotus Design. And then came the Elise. ‘The Elise was the Lotus I’d waited around so long to do. Everyone else on the team was the same. It was the perfect window in time: the right group of people, all the right age, the same interests and passion for sports cars, that’s why the car is so pure.

‘We were all so passionate about doing it. That’s how we managed to cut so many corners – I can’t believe we made a car so impossible to get in and out of. Yet all the people who worked on it were young and didn’t have back problems. As for the roof taking 15 minutes to put on – you were lucky we gave it one at all!’

Despite huge pride in his creation, Thomson didn’t own an Elise while he was at Lotus, but he did enjoy a succession of Esprits, endured a chain of Vauxhall Astra company cars, and satisfied his hot hatch lust with a Renault 5 GT Turbo. He later bought the last Elise S1 off the production line but felt so self-conscious at that time about driving a car he’d designed, he swiftly sold it. He came to his senses 15 years later and bought himself an S1 Sport 160. ‘It’s very unruly at low revs but then comes alive, banging and popping, noisy and visceral.’

A yearning to once more be back in the big car company league drove Thomson into the arms of Volkswagen-Audi as director of exterior design in the group’s studio in Barcelona. ‘It was almost like going back to school,’ states Thomson, ‘and I worked for VW, Audi, SEAT and Bentley. It was really good fun and got the juices flowing, but I did miss working with friends. I’ve always been a creative guy who loves interaction and throwing ideas around, so in 1999 when Ian Callum offered me the opportunity to work with him at Jaguar in the Advanced Design studio, I took it.

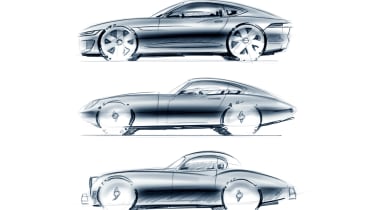

‘Ian and I had nearly 20 years of fun working together: he was never really a boss, he was always like a friend. We’d design stuff together and it was so enjoyable, all those great cars we did redefining the brand.’ That roll call includes the R-Coupe, RD6, C-X75, C-X17 (F-Pace) and I-Pace concepts, the production XK, XF, XJ, XE and F-type, the Land Rover LRX concept (the inspiration for the Range Rover Evoque), and even a concept for a computer game, the Vision Gran Turismo.

A succession of XJR and XFR company cars kept Thomson amused during his years at Jaguar – as director of design for the past couple, following Callum’s departure – but only after leaving the company in 2021 has he owned his own Jaguar, an XK120 FHC bought in the States with the help of Jaguar Classic. The Dino remains in his stable, as does the much-neglected 124 Spider and the Elise, and he attributes the rest of his current collection in part to evo’s influence – a Renault Sport Clio Trophy, a Subaru Impreza RB5 and the latest Honda Civic Type R (‘I like the fact it’s so great to drive that that overcomes its challenging looks’), while his girlfriend has a Porsche 997 GT3, and his son an E28 BMW 5-series in which he has a half share. Thomson also helped design the 2001 Honda Civic Type R while at Lotus, and his passionate belief that you should own cars you designed means that a track modified example also shares garage space.

At the time of writing, Thomson is exploring a number of employment options and is extremely upbeat about the future of motoring and car design, albeit in a different form to today. He still marvels at the good fortune of his career to date. ‘I like designing cars because I like colouring-in, essentially. I am still just scribbling on the back of envelopes, and always will be. I can’t believe that someone has permitted me to go off and turn my schoolboy drawings into real cars, and paid me to do it. It’s what I was doing as a child and I’m still doing it as an adult. I am very lucky in that respect, still stunned that I’m allowed to do it.’