Differentials explained: how does a car’s diff work?

Every car has one, but what does a differential do and what’s an LSD?

Virtually every road car is equipped with some sort of a differential and it’s vital to the way a car performs – without one negotiating a corner would be difficult. The differential’s main purpose is to allow the wheels to rotate at different speeds as when cornering the outer wheel needs to travel further and faster than the inside wheel. In a rear-wheel drive car it’s generally known as an open differential where drive is received from the engine via a propshaft and then sent through a series of gears inside the housing and out to each of the wheels. Both wheels are driven evenly but independently from one another so each wheel can spin at different speeds.

In a front-wheel drive car the differential is located within the transaxle with the principle remaining the same as for rear-wheel drive cars. All-wheel drive machinery generally add an additional differential or transfer case in order to split the drive between front and rear wheels.

The main problem with an open differential, though, is that the power tries to exit the differential in the easiest way, or through the path of the least resistance. This means that in low traction conditions if one wheel begins to slip or spin then it is likely that all of the power will be diverted to that one slipping wheel as there is nothing to ensure the balance or spread of power between the two. That's where the colloquial expression 'one tyre fire' comes from.

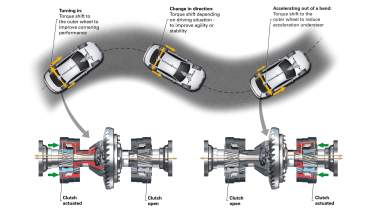

With the arrival of advanced traction control systems manufacturers try to get around this phenomenon by momentarily reducing the engine’s power or by braking individual wheels but the best solution is to fit a limited-slip differential, or LSD for acronym lovers.

> A Porsche Taycan has drifted on ice for nearly 11 miles, beating our previous world record

An LSD does exactly what it says on the tin; it limits wheel slip. When a limited-slip differential detects the two driven wheels are traveling at vastly different speeds (and therefore not cornering) it simply tries to balance them until wheel slip is reduced and therefore traction is restored. This means that both the driven wheels do the same amount of work when required, unlike an open differential.

There is more than one way to do this and here we are going to look at the most common methods of doing so from aftermarket solutions to factory, and those that dip in between.

Clutch plate LSD

A clutch or plated differential is what is often considered the most common and effective of the LSDs out there. It works in quite a complex way as inside the housing is a set of gears to transfer the power to each of the wheels like an open differential. But these gears are connected to a single pin in the centre that revolves as the differential works as normal. Next to the pin there are a series of clutches that work so that if a wheel does begin to slip it causes the pin to try and climb up against the clutches. It’s the pressure from these clutches working against the pin that forces the wheels to constantly operate at the same speed.

This kind of LSD has many benefits that other differentials cannot offer. For a start, they constantly work to keep both wheels locked at the same speed unlike others that wait for a wheel to slip before working. As a result a clutch plate LSD reacts very quickly to wheel slip and usually quite aggressively.

Also, uniquely, they work on de-acceleration as well so that as you back off, the centre pin will again work against the clutches to ensure both wheels always receive the same amount of drive whether on the throttle or not. The real beauty of this LSD, though, is that it can often be tailored to suit the car and application. The preload of the clutches and the angle the pin tries to climb against them can usually both be adjusted on most aftermarket LSDs and this gives different handling and traction characteristics.

The downside to a plated limited-slip differential is that the clutches wear out over time, so they do need some maintenance. They are sometimes considered to be a little too noisy and aggressive for a road car depending on how they are set up. However, manufacturers now tend to get around this by controlling the pressure of the clutch plates electronically rather than mechanically. This gives the best of both worlds as it’s very effective but without the harshness.

Viscous LSD

This kind of clever differential works by relying on the properties of viscous fluid to limit the amount of wheel slip. It does this by using two sets of plates that are encased in a sealed housing in the centre of the differential. The housing is filled with viscous fluid and each half of the plates is attached to each of the two driven wheels. The plates sit very close to each other with a thin layer of viscous fluid between them.

When working normally the whole assembly turns together but when one wheel begins to spin faster than the other it will, in turn, cause its half of the plates inside the differential to spin faster. As this happens, the viscous fluid between the plates will naturally be dragged against the slower-moving plates, which are next to it. This process in turn slows the slipping plates and increases the speed of the opposing plates, therefore balancing out the speed of both sets of plates and with it, the two driven wheels.

This kind of LSD is a lot softer in its operation, so is often fitted to road cars, but it has its downsides. First of all, it won’t try to balance the power between the wheels until one of them has already started slipping as during a corner there isn’t enough resistance to cause the viscous fluid to have an effect. The other major issue is that these differentials can wear over time. The viscous fluid and even the plates do not last long term, particularly if they are under heavy use due to engine power output or driving style.

Quaife ATB

The Quaife differential works in a different way to both a plated and viscous LSD. It’s what is known as a torque biasing differential and it works by using sets of helical cut gears. These gears are mounted in individual housings that allow no sideways movement and they’re also meshed to smaller gears that are linked to each of the driven wheels. As the helical gears turn they mesh with each other and in usual operation it will work as an open differential. But when one wheel starts to slip faster than the other the gears are naturally forced to bind together as they can’t divert the pressure anywhere else. The resistance as they are pushed against one another evens the balance between the gears and therefore balances the speed of the driven wheels.

It’s effective and smooth in its operation but the downside is in some circumstances it can perform like a regular open differential and become one-wheel drive if there isn’t enough resistance or load in the gears to balance. This might occur if one of the driven wheels is off the ground for example which means it will send all the power to the wheel off the ground, not the one on it. On the plus side, these differentials are reliable, feature few moving parts or bearings, do not require regular servicing.

Welded differentials

As a side note, it’s worth mentioning welded differentials. You may have heard of these before and they usually feature on drift cars. These are regular open differentials that have had the gears welded together, thus locking the axle together completely so both driven wheels will turn at the same speed all of the time.

It is cheap to do and it does aid traction as well as any aftermarket LSD in some circumstances. But the downside is that it doesn’t allow for wheels to turn at different speeds or cover a different radius, so the inside wheel is forced to do the same amount of turns as the outside wheel. This causes it to skip, jump or hop as it tries to make its way round a tighter corner so whilst it’s great for something like drifting it’s not ideal for road use.