Turbochargers explained: how does a car turbo work?

What is a turbo? How does it work? Are they a good thing, and are they here to stay in today’s electrified world?

Turbochargers have been around for many years and while they were initially more the preserve of the aviation industry, car manufacturers started experimenting with automotive applications in the 1960s and 1970s. BMW was the first European manufacturer to release a turbocharged production car – the short-lived and monumentally laggy 2002 Turbo – but others persevered and names such as Porsche and Saab became synonymous with the word turbo.

Other manufacturers caught on and it didn’t take too long for a plethora of companies to add the turbo moniker to any vehicle that was supposed to be slightly sporty. Without the turbocharger it’s likely the diesel engine wouldn’t have been anywhere near as popular and the concept of a performance diesel would never have come to fruition. These days the turbo is ubiquitous for those cars still powered by internal combustion engines and it’s almost possible to count the number of naturally aspirated cars still on sale on the fingers of one hand.

> How to make your tyres last longer

The crux of the matter is that turbochargers are able to massively increase the power output of an engine but without the same kind of emissions that would be associated with a naturally aspirated engine producing the same power. These days it’s not unusual to see a four-cylinder turbocharged engine developing 300 or 400bhp, yet still being more economical and offering lower emissions than a larger naturally aspirated unit.

However, turbochargers aren’t without their downsides. Traditionally the main problem associated with turbocharging has always been ‘lag’, essentially the delay felt after pressing the throttle before power comes in. Particularly in the early days, turbos had a bad reputation for their slow response but over the years new technologies have improved the way turbos perform to counter this side effect.

What is a turbocharger?

With petrol engines you need three elements to create the controlled explosions that take place in each cylinder – air, fuel and a spark. Add more air and more fuel and there will be a larger explosion but there comes a point in naturally aspirated engines where the limiting factor becomes the amount of air the engine is able to ingest. Which is where the turbocharger comes in, as it can force more air into each cylinder, creating a bigger explosion and more power.

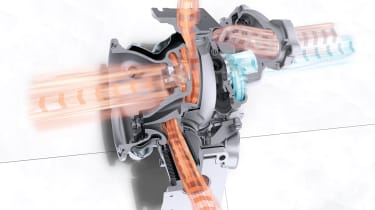

A turbocharger is effectively a device powered by the exhaust gases exiting the engine via the exhaust manifold to force more air into the combustion chamber. Inside the turbo is a turbine wheel and as the gases pass by on the way out into the exhaust pipe the wheel spins. Its rotation is directly related to the engine’s rpm so its speed will increase as more exhaust gases are produced.

This spinning turbine wheel is located on a shaft and on the other end in a separate enclosed housing sits a compressor wheel. So as the turbine wheel spins, the compressor wheel spins and by doing that it draws in vast amounts of fresh air. This air is then compressed into positive boost pressure as it is sent into the compressor housing and forced out towards the engine’s inlet. The compressed air is then mixed with more fuel than usual before being ignited to produce a more powerful explosion, therefore creating more power.

> Hybrid car technology explained – mild-hybrid, 'self-charging' and PHEV

What is turbo lag?

Turbo lag is the one major downside to turbos. As the turbine wheel works on the speed and quantity of exhaust gases exiting the engine it will only make positive boost pressure once it is up to speed.

It is the dead time when the engine is still trying to produce enough gases to spin the turbine wheel fast enough that creates what is known as boost threshold, or lag, as you wait for it to respond.

The same thing will happen during gear changes as the throttle is momentarily closed shut. It isn’t for long but it’s enough to have an impact and make the turbo fall off its optimum rpm level, meaning engine revs must build up again before the turbo will produce boost pressure.

Over the years manufacturers have made great strides in improving throttle response from turbocharged engines using ceramic bearings to allow the turbine to spin more freely, twin-turbo set ups, twin scroll turbochargers and even electric motors to keep the turbo spinning when there aren’t enough exhaust gases to fully do the job.

What is twin-turbocharging?

It makes sense that bigger engines are capable of producing and consuming larger amounts of fuel and air, and twin-turbocharging takes advantage of this in several different ways.

Firstly, there are basic setups that use two identical turbochargers to work in unison, each doing an equal share of the work. The boost they produce is then amalgamated and sent towards the inlet manifold.

However, because bigger turbochargers are less responsive at low revs and smaller turbochargers run out of puff higher up the rev range, a sequential turbo setup is designed to improve both lag and response. It does this by using valves to specifically direct the engine’s exhaust gases. In the lower rev range they are diverted towards one small turbo that produces boost quickly to give the engine low-down power. As the revs rise an electronically controlled valve is then triggered at either a specified boost pressure or a certain rpm point. Then, the larger quantities of exhaust gas are seamlessly diverted towards a second, larger turbocharger that takes over from the smaller unit. The result is the best of both worlds as the two turbos work with each other to create a single wave of power.

What is a twin-scroll turbocharger?

In principle a twin-scroll turbocharger works in the same way as any other turbocharger. However, it makes much better use of the engine’s exhaust gases, or more specifically, how and when they exit the engine. Conventional engines never fire all the cylinders at the same time, therefore exhaust gases exiting the engine come in pulses.

These pulses all meet in the exhaust manifold just before entering the turbocharger. The trouble with this is that when these varied and mixed pulses of gas meet it disrupts the flow and therefore decreases the speed of the gases. This decrease of speed in turn means the exhaust wheel turns slower than it could do, reducing the efficiency of the turbo and increasing the response and lag.

However, by dividing the exhaust manifold up into separate sections and keeping the gases apart all the way until they pass the turbine wheel, it is possible to feed the turbo in alternating pulses that don’t interfere with each other. This way, exhaust gases from certain cylinders will only combine for the first time once they are in the exhaust pipe. This creates a more fluent gas speed and the results are a turbo that spins quicker, therefore reducing lag.

What does an intercooler do?

The temperature of the compressed air as it exits the turbocharger on its way to the engine is relatively high, so if it can be cooled it will become denser, which means it can be mixed with more fuel for a bigger explosion. It’s the job of the intercooler to do this, and by passing the boost pressure through a sealed core it works in just the same way as a normal car radiator does by using passing airflow to cool the charge.

Alternatively, some cars use a water cooler, or charge cooler as it is known. This works in the same way but instead of using airflow to cool the sealed core it uses water or coolant, which is kept circulating around the core using a separate pump and circuit. It also has its own radiator to keep the fluid cool. This is crucial, as the downside to water-cooling is that if the fluid gets too hot it becomes ineffective and ultimately reduces power as the air isn’t sufficiently cooled.

How is the turbo regulated?

Eventually, the engine will reach a point when it can’t, or won’t, consume anymore of the boost produced by the turbo, so it must be regulated. It is the job of the wastegate to do this by creating another exit for the exhaust gases to escape before they reach the turbine wheel.

This separate escape path is a small trap door that opens at a set pressure to stop the turbo over-spinning and producing too much boost. A byproduct of this is that trademark turbo blow-off valve sound, which varies in characteristics depending on the amount of boost at play and the type of wastegate used.