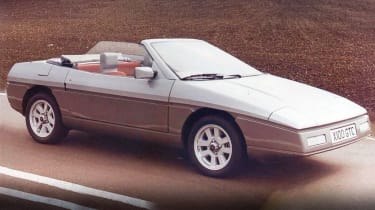

Lotus M90 Elan – Dead on arrival

Financial issues, the death of the company founder and a change of drivetrain ethos at a Japanese giant all played their part in the demise of this 1980s concept for a rear-driven Elan

During the 1970s Colin Chapman steered Lotus upmarket, selling the Seven to Caterham and killing the original Elan in order to introduce the upmarket Elite coupe of 1974, briskly followed by its Éclat sister and the mid-engined Esprit. However, these fancier models weren’t enough to run the Hethel factory at capacity, which is why Mike Kimberley, Lotus’s chief engineer and later managing director, asked designer Oliver Winterbottom to start work on a cheaper, 2+2 sports car, based on a cut-down Elite chassis.

The project promptly stalled for lack of finances, only to be re-ignited at the end of the ’70s when Chapman agreed to a new entry-level car if Lotus could persuade a larger manufacturer to provide a cost-effective powertrain. Kimberley set about finding a big fish to whom Lotus could provide know-how from its new engineering consultancy in return for hardware, and in late 1980 sealed a deal with Toyota. Lotus would undertake development work for the Japanese giant (engines initially, though they would later work on the Supra and, according to unconfirmed rumour, the original MR2) in return for which Hethel would receive the 2-litre four and RWD drivetrain from the Celica.

With a deal done, the project was assigned the codename M90 and Winterbottom was left alone during 1981 to refine the style and packaging of coupe and roadster versions. Unfortunately, the early ’80s weren’t kind to Lotus and in December 1982, as the company ran dangerously short of money, its problems were compounded when Colin Chapman died of a heart attack. The M90 was the last Lotus project to receive his input.

> An uncomfortable journey in a Lotus 2-Eleven – evo Archive

In the wake of its founder’s death, Lotus teetered on the brink of collapse until Kimberley persuaded Toyota to take a 22-and-a-half per cent stake, quickly followed by major investment from David Wickens of British Car Auctions, who bought up 29 per cent and became the company’s new chairman. With a fresh start for the company the M90 was given a renewed sense of purpose. The wheelbase was chopped to make it more agile, the Toyota engine was now the 1.6-litre 16-valve unit from the AE86, and the design was refined with a sharper, shorter nose and the slender rear lights from the Aston Martin Lagonda. The first running prototype, a roadster, was completed in March 1984.

On paper M90 was a promising idea, what with a zingy little engine driving the rear wheels and a target weight of just 860kg. Unfortunately, the finished car didn’t live up to this promise, blighted by poor chassis rigidity and a wedgy design that risked looking dated by the time it went on sale. Worse yet, there was a feeling within management that the car was too predictable, at odds with the Lotus spirit of innovation.

Meanwhile, the Toyota consultancy had allowed senior Lotus engineers to compare the existing rear-drive Corolla to an early example of its front-wheel-drive replacement, and their conclusion, cemented by findings on projects for other car makers, was that the future would be pulled rather than pushed. Without telling the M90 team, Lotus management asked Peter Stevens to work up a new styling theme for a possible front-wheel-drive sports car, and in early 1985 the increasingly unloved M90 was brought together with a full-size model of Stevens’ proposal for a management review. The board voted to proceed with a front-driven car and the rear-wheel-drive M90 was dead.

The lone prototype was stashed in a Hethel warehouse until 1998 when, as part of an auction of unwanted assets, it was sold to an American collector. In what might pass as a happy ending for this doomed one-off, the car was subsequently restored and made road legal, while its usurper would evolve – via a GM takeover, a complete redesign and a switch to Isuzu power – into the M100 Elan of 1989.