Sustainable fuel v unleaded petrol: we dyno test the impact on car performance

Considering running your car on sustainable fuel? We’ve dyno tested the first publicly available option to see the effect on power, torque and emissions compared with unleaded petrol

In June last year, fuel specialist Coryton launched the first sustainable gasoline to be made publicly available in the UK. Called Sustain Classic Super 80, it’s a biofuel with a 98 RON (octane) rating and is certified to deliver an overall greenhouse gas saving of 65 per cent compared with fossil fuel. Motorsport has been an early adopter of sustainable fuels and Coryton has created over 400 biofuel formulations for different applications, one of which powered Prodrive’s Hunter T1+ to podium places on the 2023 and ’24 Dakar rallies.

Coryton is betting on classic car owners being early adopters too; the formulation of Sustain Super 80 is aimed primarily at them. It combines 80 per cent sustainable biofuel (hence the name) with 20 per cent fossil fuel and less than one per cent ethanol. Ethanol is now up to ten per cent in regular unleaded (E10) gasoline and remains at five per cent in superunleaded (E5) formulas; although it helps lower emissions it attacks non-ferrous metals, rubbers and plastics, which are often found in older car fuel delivery systems.

> Synthetic fuels explained: is there such a thing as carbon neutral petrol?

Sustain Classic Super 80 is a drop-in fuel, which means it can replace or be mixed with any pump gasoline. Intrigued to see what effect it would have on power, torque and emissions, we took three of our long-term test cars and dyno tested them on regular pump fuels and then Super 80. This is different from what we did back in issue 306 when we reported on a back-to-back driving comparison of two Mazda MX-5s. In that test, the Coryton sustainable fuel was formulated to match regular E10, 95 RON unleaded, so its sustainable element was supplemented with 10 per cent ethanol, as per the pump fuel.

There’s currently only one site where you can pull up and fill up with Super 80 and that’s Motor Spirit at Bicester Heritage in Oxfordshire, where it costs £4.65 per litre. That’s considerably more expensive than premium fuels such as Shell V‑Power, which are typically between £1.60 and £1.90 per litre. Coryton offers home delivery in barrels of various volume, at a cost.

How is sustainable biofuel made?

So-called second-generation biofuels are manufactured from agricultural waste, such as straw or by-products and waste from crops (‘slops and tops’) that wouldn’t be used for consumption. By using them, the fuel utilises carbon that already exists in our atmosphere and recycles it. Any material that can be fermented can be used to make biofuel, and the first product you get is ethanol. This is then degassed to remove the oxygen and water, leaving only hydrogen and carbon. These are then processed through a series of catalysts that turn them into a liquid hydrocarbon.

Coryton’s Sustain Classic range offers three formulations with varying levels of renewable biofuel and therefore different levels of greenhouse gases (GHG) savings. Sustain Classic Super 80 is a blend of 80 per cent sustainable fuel and 20 per cent regular fossil fuel that saves at least 65 per cent of GHG and costs from £4.65 per litre. Super 33, also 98 RON, has 33 per cent renewable content, saves 25 per cent GHG and costs from £3.80 per litre. Racing 50 is a 102 RON fuel that’s 50 per cent renewable, saves 35 per cent GHG and costs from £5.25 per litre. All three are low-ethanol and come with an additive package that, like those offered with fossil fuels, prevents deposits and helps keep the fuel system clean.

Our test

We selected three cars from our long-term fleet with different engine configurations: the Toyota GR Yaris with its 1.6-litre, three-cylinder turbo, the Caterham Seven evo25 (based on the Seven 420) with its 2-litre, naturally aspirated ‘four’, and the 992-generation Porsche 911 Carrera GTS, with its 3-litre, twin-turbocharged flat-six. Each arrived at the dyno on a different pump fuel: the Toyota on BP Ultimate unleaded (97 RON), the Caterham on Shell V‑Power (99 RON) and the Porsche on BP regular unleaded (95 RON).

The dynamometer at Litchfield Motors near Tewkesbury is a German-built MAHA MSR500, an industry-standard machine used by the likes of Porsche and BMW. It has four-wheel-drive capability, allows test speeds of up to 186mph and is ideal for very high-performance cars. It corrects for not only mechanical losses but also atmospheric temperature and pressure, so results are consistent. Unlike many dynos, it measures emissions too.

First up is the Toyota. There’s always something thrilling about watching a car being wrung out on a dyno, hearing revs build against the load, the engine digging in with maximum torque before the note thins out as the revs soar towards peak power and, finally, the abrupt stutter of the engine against its limiter. Then there’s the sound of the engine on the overrun and the tyres on the rollers gradually dropping in tone until finally, until, like the last rotations of a roulette wheel, the wheels come to a halt and the numbers are revealed.

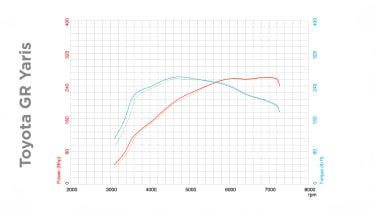

Toyota GR Yaris

| Power | Torque | |

| Manufacturer claims | 257bhp @ 6500rpm | 265lb ft @ 3000-4600rpm |

| BP Ultimate (97 RON) dyno results | 261.2bhp @ 6765rpm | 262.4lb ft @ 4210rpm |

| Coryton Sustain Classic Super 80 dyno results | 258.9bhp @ 6755rpm | 252.8lb ft @ 4280rpm |

On 97 RON BP Ultimate, the Yaris exceeded the manufacturer’s quoted power by 4bhp and was 3lb ft down on torque, though the latter was expected. Litchfield’s technical manager, Dan Cook, who conducted all the dyno runs, says that the claimed torque includes some overboost, which kicks in if you snap open the throttle from 3000rpm. The dyno runs see power build from lower revs.

On Sustain Super 80, power was down 2.3bhp compared with BP 97, while peak torque was down by 10lb ft, and a little more than that up to 3000rpm.

In terms of emissions, on a 70mph steady-state run, the Yaris was very clean on BP Ultimate, with HC (unburnt hydrocarbons) and NO (nitrogen oxides) barely registering, just a few parts per million (ppm) for each. Running on Super 80 reduced the HC by about 1ppm and increased the NO by about 3ppm, so a very small change. When it came to dynamic emissions, there was a doubling of HC on Super 80, though this was from a low 20ppm to 40ppm, so still a very small number, while NO was barely changed.

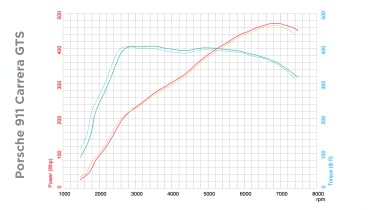

Porsche 911 Carrera GTS (RWD, manual)

| Power | Torque | |

| Manufacturer claims | 473bhp @ 6500rpm | 420lb ft @ 2300-5000rpm |

| BP unleaded (95 RON) dyno results | 471.9bhp @ 6900rpm | 406.8lb ft @ 3480rpm |

| Coryton Sustain Classic Super 80 dyno results | 465.5bhp @ 6860rpm | 406.3lb ft @ 2950rpm |

On BP 95 unleaded, the 911 was just 1bhp shy of Porsche’s claim. Torque was about 13lb ft down but, as with the Yaris, this is because the claim includes snap-throttle overboost. On Sustain Super 80, it was 6.4bhp down on BP 95. Peak torque was almost identical but delivered at a different point, Super 80 delivering more up to about 3000rpm, where it peaked, BP 95 delivering a little more thereafter.

On the steady-state run, Super 80 reduced NC and NO to virtually zero. Admittedly, on BP 95 HC was only 7ppm and NO just 1ppm, but it was a reduction nonetheless. Dynamically, there was hardly any change in HC and NO emissions, with little more than 2ppm between the fuels.

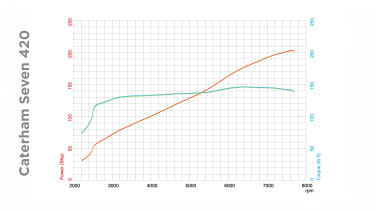

Caterham Seven 420

| Power | Torque | |

| Manufacturer claims | 210bhp @ 7600rpm | 149.7lb ft @ 6300rpm |

| Shell V‑Power (99 RON) dyno results | 203.5bhp @ 7635rpm | 145.3lb ft @ 6415rpm |

| Coryton Sustain Classic Super 80 dyno results | 202.9bhp @ 7635rpm | 146.2lb ft @ 6415rpm |

On Shell V‑Power, the Caterham was 6.5bhp down on the maker’s claim, while peak torque was about 4.5lb ft down. On Sustain Super 80, the figures were almost identical, the power and torque curves virtually overlaid, with power less than 1bhp down, torque less than 1lb ft up.

However, there was a significant difference in emissions. Running Super 80 reduced HC by nearly 50 per cent, from 82ppm to 44ppm, while NO remained relatively unchanged. It appears that the Toyota and Porsche, configured to meet ultra-low emission standards, have little to gain, but on less sophisticated cars Super 80 has a larger effect. The dynamic test was inconclusive, though, with a large variation in results run to run on both fuels.

The results

If you’re concerned about your carbon footprint, our test shows you can use Sustain Classic Super 80 just as you would a regular pump fuel, and save at least 65 per cent of the CO2 produced by fossil fuels.

The Toyota and Porsche, with their state-of-the-art engine management and emissions control systems, didn’t get the uplift from Super 80’s 98 RON rating, coming up a fraction shy on the power achieved on 97 RON unleaded in the Toyota and the 95 RON unleaded in the Porsche. In terms of torque, the peaks on Super 80 in the Porsche were almost identical and in the Toyota down just a few per cent. Emissions were barely altered, and after the dyno runs we drove both cars on Super 80. Subjectively, there was perhaps the slightest softening on snap-open throttle response in both but otherwise performance was indistinguishable, and economy appeared to be the same too.

The Caterham, with its less sophisticated engine management and emissions system, delivered virtually the same power and torque on Super 80 as on 99 RON unleaded, but we saw a notable drop in hydrocarbon emissions running Super 80, down by almost 50 per cent in the steady-state test. Unfortunately, inconsistent results in the dynamic emissions test didn’t corroborate this, but it appears that cars with less advanced engine management – i.e. older cars – benefit most from Super 80.

Coryton hopes to make Super 80 more widely available, increasing its popularity, which would help bring down the price. The CO2 savings it brings are good for the environment, while with its low ethanol content and specific additive package tailored to older cars, you can think of it as superunleaded for your classic.

Can efuels save ICE?

There has been much talk around sustainable fuels and how they may allow a stay of execution for internal combustion engine cars. The EU, lobbied by Germany, will now allow some new ICE vehicles to be sold beyond the 2035 Euro cut-off, provided those vehicles are fuelled exclusively on carbon-neutral fuel.

Qualifying fuels would have to be 100 per cent sustainable. Biofuels could get there (see Q&A), while so-called efuels, such as that being produced by the Porsche joint-venture plant in Chile (see evo 309), are by their nature wholly sustainable. They are created from carbon captured from the atmosphere or an industrial process, which is then synthesised with hydrogen extracted from water, and all the energy required for the complete process comes from a renewable source, such as solar, wave or wind.

If 100 per cent carbon-neutral fuels became available in the UK, currently this wouldn’t make any difference because the UK’s 2035 ban on new ICE vehicles contains no EU-style dispensation.

Q&A: David Richardson Business development director, Coryton

evo: Why do you blend your biofuels with fossil fuel? Can your biofuel be 100 per cent sustainable rather than 65 per cent, i.e. could a fuel made purely from biomass be 100 per cent carbon neutral, to satisfy EU requirements for allowing ICE vehicles beyond 2035?

DR: At the moment we are limited with the amount of sustainable chemistries required to make high-performance fuels. In some applications, this can be made easier with the use of ethanol, as it’s a really good blending component, and in these cases a 100 per cent non-fossil-derived fuel can be achieved – and we do offer this. But where alcohols are an issue, specifically for the classics market, it makes it a little more difficult. Either you add a significant amount of cost, reduce traceability of the sustainable components, lower the sustainability, or lower performance. It’s a balancing act and we’ve taken a more pragmatic approach to our fuels for the time being.

evo: Sustainable biofuels are traceable to confirm their sustainability. What was the origin of the bio element of the fuel we tested?

DR: It was derived from agricultural residues that were otherwise destined for landfill.

evo: What are the most common bio elements in Sustain Classic Super 80?

DR: It’s what we refer to as a ‘bio-hydrocarbon’ – this itself is not a finished gasoline as you know it, so we also add bio-ethers, which are derived from ethanol.

evo: Apart from Motor Spirit at Bicester Heritage and direct from yourselves, is Sustain Super 80 available anywhere else?

DR: Not at the moment but we’ve set ourselves an ambitious goal to have six to twelve pumps around the UK, along with two to three more distribution points for our barrelled fuels, within 2024.

evo: If it’s delivered direct, how much is Sustain Super 80 per litre? And is there a delivery charge and a deposit on the cans?

RD: The fuel used for the test, Sustain Classic Super 80, currently retails on the pump at £4.65 per litre; drummed this pushes the price to between around £4.85 and £5.10, depending on the drum size. Delivery is dependent on how much is shipped and to where in the country, but somewhere in the region of £120 for up to 800 litres.

evo: Are there any similarities between the additive package in Sustain Super 80 and, say, Shell V‑Power?

RD: There will be similarities such as detergents, but thereafter we’ve tailored these fuels specifically to look after classic vehicles by adding additional additive technologies to stop oxidisation and the interaction with metals.

Thanks to all at Litchfield and Coryton for their assistance with this feature.

This story was first featured in evo issue 320.