Aston Martin DB4 GT Zagato Continuation review

Just 19 Aston Martin DB4 GT Zagato Continuations have been built, honouring the 1959 original. We drive this multi-million pound recreation.

Back in the ’50s and ’60s, when Aston Martin was owned by industrialist David Brown, he was famously telephoned by a customer who was keen to buy a new DB5, but less eager to pay full retail price. When asked by said chap if he could purchase the car at cost price, Brown is reputed to have replied: ‘Of course! That will be £1000 over list, then.’

How times change. Six decades later Aston Martin is once again building ‘DB’ models at Newport Pagnell, albeit in ultra-limited runs of special ‘Continuations’. This began in 2016 with the build of 25 fabulous DB4 GTs and, er, continued last year with the completion of 19 exquisite DB4 GT Zagatos. Next in line is a run of 25 brand new Goldfinger DB5s, with other projects in the pipeline.

Quite what the redoubtable Mr Brown would have made of the whole continuation phenomena is open to conjecture, but I have a feeling he would be entirely supportive of the pricing strategy, which somewhat remarkably positioned the DB4 GT Zagato Continuation as the most expensive new car in the world.

Forming one half of the DBZ Centenary collection – 19 pairs of cars built to mark Zagato’s centenary and celebrate the Italian carrozzeria’s enduring collaboration with Aston Martin – Aston’s most avid collectors were required to part with a knee-knocking £6m (plus local taxes). In return they first received their DB4 GT Zagato, followed by an all-new DBS GT Zagato just as soon as the exotically bodied DBS Superleggera-based machine enters production at Aston Martin’s Special Ops facility at Wellesbourne.

Of course, the Centenary collection’s stratospheric price tag is almost entirely a function of the value of original DB4 GTZs, which currently sit somewhere north of £10m. Whether you go Dutch on the Centenary collection’s £6m sum and say the Continuation accounts for half of it, or apportion all of it to the DB4 and assume the DBS completes the greatest BOGOF deal in history is entirely academic. Suffice to say it’s all so far beyond the realm of even today’s top-tier hypercar pricing that all you can do is shake your head and marvel at how pleased you’d be if you got dealt either of these Zagato-badged wonders in a hand of Top Trumps.

What we do know is each of the 19 DB4 GTZs is the mouth-watering product of 4500 hours of painstaking craftsmanship by the team at Aston Martin Works. Even so, it’s all too easy to be cynical about a programme that makes new examples of old icons. Cynical, or perhaps uneasy at the possibility that in doubling the original number of DB4 GTZs (not to mention adding to the run of four ‘Sanction II’ cars built from regular DB4 donor cars with Aston’s blessing in 1989), these Continuations somehow muddy the waters in the same way admittedly lesser and far more numerous copies of Shelby Cobras and Ford GT40s have done in the past.

See one of these cars in the metal and you quickly realise that fear is very much misplaced. OK, so there has been a 60-year hiatus in production, but these are factory-built cars, built from all-new components, made in the exact image of their ancestors and blessed with enhanced performance, quality and reliability.

You’d need to have a heart of stone not to appreciate the magic that surrounds these cars. Not only built in the same place as its legendary 1959 forebear, but made with the same age-old skills. Skills that have found a new lease of life in the youthful enthusiasm of a dozen apprentices taken on by Works since the Continuation programme began.

With bodywork hand-beaten by Zagato’s artisans from flat sheets of thin-gauge aluminium and shaped by eye to follow the contours of wooden bucks, no two panels were ever exactly the same. Indeed, when subjected to scrutiny those original cars were often found to be somewhat asymmetric!

This time around the bodies are fashioned in-house at Newport Pagnell. Laser scanning of multiple original cars meant Works could create a digital buck as a master reference, ensuring surfaces that were perfectly symmetrical while remaining faithful to Ercole Spada’s wonderful lines. Those paper-thin (1.2mm!) panels were then attached to the DB4’s ‘Superleggera’ structure and meticulously hand-finished prior to going into Works’ state-of-the-art paint booths. All 19 cars were completed at the very end of 2019, but evo was fortunate enough to visit Works at the height of production and witnessed half the production run in various states of completion. From raw alloy carapaces still bearing smoothing scuffs and deft abrasions left by the supremely skilful panel beaters to impossibly glossy painted cars sitting squat and perfectly poised on beautiful Borrani wire wheels. It could have been a scene straight from 1959.

Like the chassis structure and bodywork, the running gear borrows its design from the original car, but benefits from advances in engineering methods and material science, not to mention the continual performance and reliability developments by world-renowned marque specialists such as RS Williams. More of which in a moment.

Due to legislative restrictions, all 19 GTZ Continuations were marketed, built and sold for track use only. That said, for those who wish to drive their Zagatos on the road, Ray Mallock Limited (RML) helpfully developed a post-registration compliance kit that will pass the Individual Vehicle Approval (IVA) test. It’s almost like it was planned…

Sadly, Works’ development car isn’t road-legal, but fortunately we have Aston Martin’s Stowe test track on which to play. Nestling discreetly within Silverstone’s GP circuit, it’s a great place to get a feel for a car, with plenty of opportunities to fling it around and a couple of modest straights to punch through the gears.

Walking up to the bright red Zagato, tiny ignition key in hand, is a slightly surreal moment. Not due to its value, but because it feels like the vanishing point where six decades of history don’t so much collide as come full circle.

This particular Zag has done plenty of laps around here, largely in the hands of Aston’s factory race driver and three-time Le Mans class winner, Darren Turner. Despite nods to modern safety, such as a hefty lattice-framed roll-cage, slightly incongruous-looking carbonfibre seat, full harnesses and a fire system, it’s very much an old-school car to climb into.

Hook your index finger through the small loop, push the button and the lightweight door swings eagerly on its hinges. The interior is plain, with an array of white-on-black Smiths dials to cast your eyes over. In your hands is the large-diameter steering wheel with thin wooden rim, while the equally spindly gearlever is topped with a small teardrop-shaped knob.

Nothing is servo-assisted so there’s a physicality to all the pedals and major controls. Initially this fosters a sense of deadness, at least when you’ve become used to the urgency, ease and general brightness of modern power-assisted cars. However, once you go to work, the car truly comes to life in your hands.

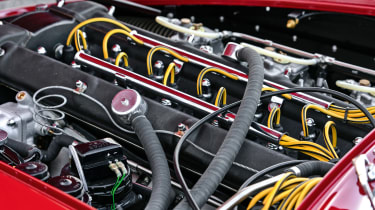

From the moment you turn the ignition key you’re drawn into the intoxicating process of driving. Fuel pumps tick and rattle from the tail of the car as they prime the bank of triple Weber carburettors slung from the right-hand side of the classic Tadek Marek-designed twin-plug straight-six. Displacement is up by a litre over the original version, lifting capacity to 4.7 litres, power to a solid 380bhp (from 314bhp) at 6000rpm and torque to an equally impressive 360lb ft (up from 278) at 5000rpm. These are big numbers for a car weighing a little over 1200kg and rolling on rims that are a scant five inches wide and wrapped by historic racing tyres.

Thanks to the track-only nature of the car, its suspension and gearbox are competition items. That’s to say rose-jointed for maximum feel and minimal compliance, and non-synchromesh for quick shifts and durability. Together with the race-raw motor, which spits and snorts impatiently, the first few laps are a raucous and rather overwhelming affair.

This car is anathema to the modern high-performance driving experience. You are literally responsible for every single input and operation. No nonsense, no driver aids and no place to hide. Right from the off you’re put to the test, slotting home first gear with a kerchunk, then easing away with measured throttle so as not to flood the generous float chambers of those huge Weber carbs.

For a while you flounder. If you’ve never driven a ’50s or ’60s car before, all your conventional reference points are useless. Even if you have, it’s a struggle to dial yourself into the machine. Go is prodigious, but grip is very, very modest, so it’s easy to overwhelm either end of the car if you’re oafish with your inputs. Take a breath and wind things back a bit and slowly you begin to establish a set of boundaries. Coax the steering and you find some grip to lean on. S-q-u-e-e-z-e the throttle and it sits down and finds more traction. Meld those two inputs and suddenly your right foot has as much say over the Zag’s trajectory as your hands.

It’s a bit like driving on snow; if you’re early, smooth and sensitive with your inputs you can transfer weight forwards on the way in and rearwards on the way out of corners. This helps reduce the front tyres’ workload when it comes to making an initial direction change, and in turn enables you to use the rear wheels (and throttle!) to steer your course onto the next straight.

Shifting gear is a lesson in measured aggression. Dither and you’ll crunch and grind your way through a box of neutrals, but hammer the lever through the gate and it feels too brutal. The sweetest shifts are delivered with a Bruce Lee-like one-inch punch, with the lever whipping through the gate like a switch. Downshifts need some deft pedal work, too, ideally a double declutch blip-shift rather than a regular heel-and-toe.

Braking is perhaps the trickiest to master. Not because the brakes are weak, but because there’s no ABS and modest grip to play with. You have to recalibrate your brain to long braking distances. Partly because the Zag really does romp along, and also because it is happiest stopping in a straight line. Brake too late, or simply try to extend your braking effort towards an apex and you’ll feel a wheel begin to lock up. It’s about as far from the smash-and-grab braking style encouraged by current high-performance road and race cars as is possible to get.

You might expect Aston Martin Works to be ultra-protective about this precious car. You certainly wouldn’t blame it. Yet much to my amazement Works boss Paul Spires lets me enjoy lap after lap. Lots for photography and lots more for the hell of it. I think it’s fair to say I got a bit carried away, but in the process of chewing through a large portion of the skinny Dunlop Racing tyres’ tread I got to know the Zag very well indeed.

Part of me is left thinking it perhaps has a little too much performance for its own good, for that 4.7-litre motor is a dominant force. Another part of me thinks the dog ’box and rose-jointed suspension would be too much for road use should you elect to do RML’s post-registration IVA test. But then the racer and romantic in me thinks it would be pretty epic to drive one of these awesome cars to Le Mans Classic, beat some Ferraris, then drive home again. Which is, after all, what the originals were designed to do.

The business of remaking classic icons is controversial and the sums of money involved are madness. At least to all but those who can afford them. Still, in the case of this DB4 GT Zagato the end result is something undeniably magnificent. While the latest wing-festooned wedges of carbonfibre chase downforce and lap times, this freshly minted DB4 GTZ shuns such binary brutalism and instead rejoices in the style, emotion and dynamics of a golden age. As a creation to covet and a car to connect you to an almost overwhelmingly pure, tactile and rewarding driving experience, it is just about perfect.