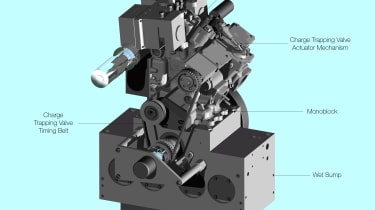

Lotus Omnivore at Geneva

Lotus revealed its no-smoke two-stroke engine at Geneva

Lotus revealed its intriguing Omnivore engine concept at Geneva, hailing it as, among other things, a way of making large-capacity piston engines very efficient.

It's a tri-fuel engine, able to run on methanol, ethanol, petrol or any combination of the three, but methanol is the greenest of the three because it can be obtained by combining hydrogen with atmospheric carbon dioxide. This still requires a hydrogen source, something exercising many industry minds in the thrust towards electric fuel-cell cars, but methanol is a much more efficient way of storing energy than hydrogen is. 'It shouldn't really be a liquid,' says Lotus engineer and Omnivore developer Jamie Turner, ' because it's such a low-mass molecule. But the polarity in the molecules pulls them together.'

The Omnivore is a two-stroke engine, but not like two-strokes we’ve known in the past in which a chunk of the intake charge goes straight out of the exhaust port at certain speeds. There's no primary crankcase compression here; the intake port leads straight into the cylinder and the charge is forced in by a supercharger. A rotary cam operates an exhaust-port flap to keep the charge where it's supposed to be, its timing variable by means of an extendible hydraulic ram to suit speed and load.

This is a direct-injection engine, and uses the HCCI – Homogeneous Charge Compression Ignition – principle. At least it does 75 per cent of the time; 'We haven't yet been able to make it idle,' says Turner. So a conventional spark plug takes over when needed.

For HCCI an engine needs a variable compression ratio, which the Omnivore has by means of a movable 'puck' in the combustion chamber (a simple solution made possible by the two-stroke's lack of conventional valves). This can vary the ratio between 8:1 and 50:1, although in practice it will never need to go that high.The advantage of making fuel self-ignite under great pressure, as a diesel does, is that all the fuel ignites simultaneously so there's no flame front. And that means there's no knocking or pinking, so the engine can be designed to get the most possible energy out of the fuel. Methanol is best here, because it burns less violently than the heavier alternatives.

Because this two-stroke doesn't use the crankcase for compression, the Omnivore can have a conventional wet oil sump. Two extra piston rings at the bottom of the piston ensure the oil mist stays away from the inlet port.

So far, the Omnivore exists mainly as a computer model, but the first real, single-cylinder example will fire up in the next two weeks. 'It should be very quiet, unlike a normal two-stroke,' says Jamie Turner, 'and theoretically it can be more powerful than production engines are now. This concept might allow very large-capacity engines with good fuel consumption, so it would be good for premium cars. People still buy capacity, because they equate it with status.'

Click this way for more from the Geneva motor show.